Graphic Histories No. 1: Visual storytelling

This is installment one for my independent study course, Graphic Histories, in which I learn more about the tiny-but-existent field of Graphic Histories (think: a historical monograph in graphic “novel” form) from graphic novelists, historians, and educators.

Presenting dense subjects with words and pictures together makes the concepts more accessible to non-academic readers, which is why, as a student of public history, the field caught my interest. For our society to apply the lessons of history, we first have to learn the history. Too often, the most profound insights of academic research live behind paywalls, buried in dense, expensive manuscripts, and are taught in higher-education classrooms. Public history concerns itself with making historical research accessible to people outside academia, and cracking that nut often means reducing word counts, introducing images, and moving documents out from behind paywalls. The authors of Making Comics and Unflattening — two graphic books about pedagogy — argue that communicating with images is about more than making things easier for the reader: The act of illustrating reveals new insights to the creator, enabling a more profound exploration of the subject. Pursing a research topic in this way requires a shift in relationship to learning: creating space for a two-way relationship with the creation and viewing the process of learning as expansive.

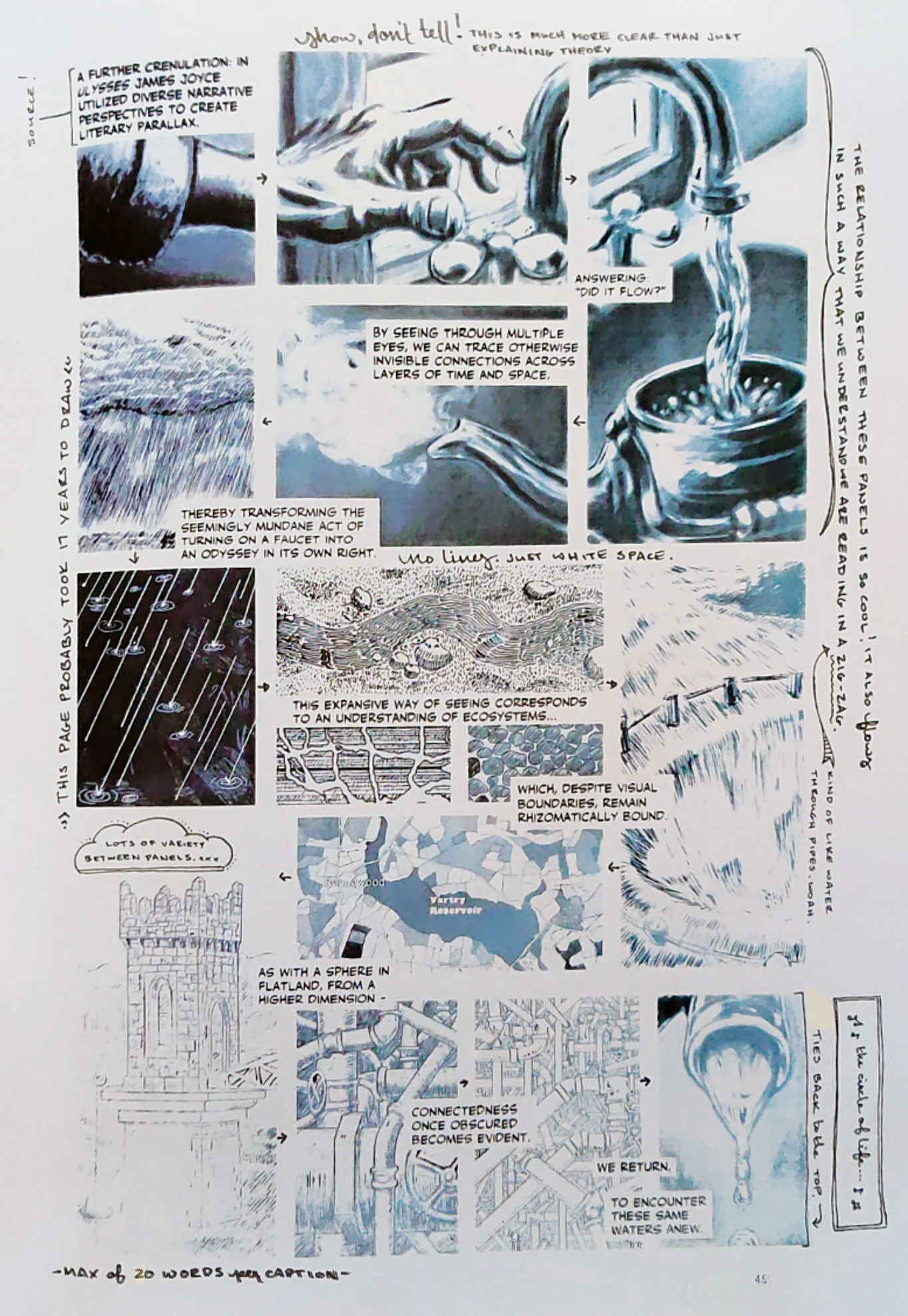

Visual annotation of a page of Unflattening by Nick Sousanis. I loved this page for a few reasons: 1) the panels flowing into each other, 2) the way the visuals guide you naturally to read in a zig-zag pattern, 3) a variety of graphic styles used on a single page (which I probably wouldn’t do, but find fun), and 4) white space instead of lines as panel dividers.

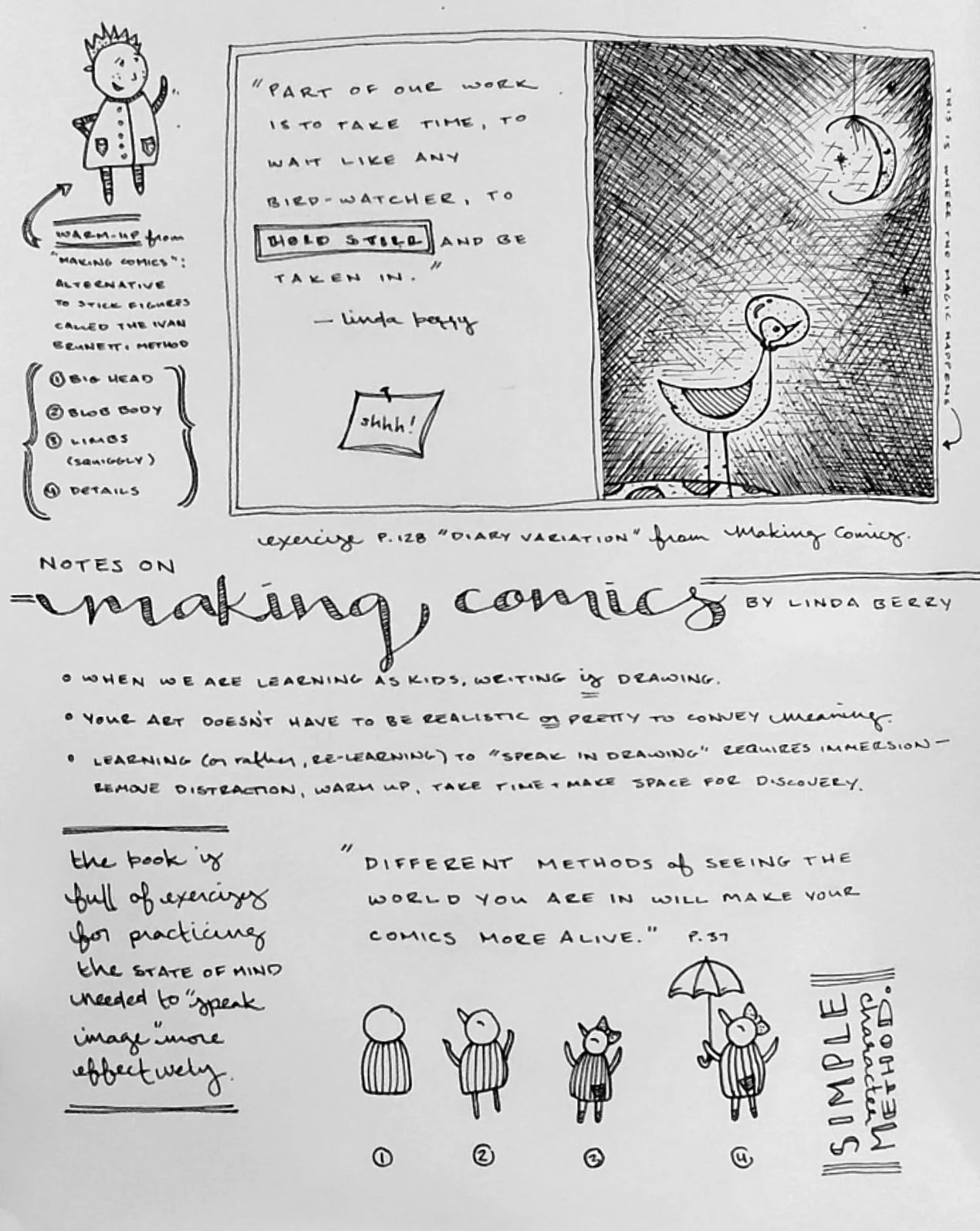

Art aficionados know that interpreting visual art is all about quiet staring: Making mental space and taking the time for details to pop out and stories to tell themselves through the picture. Lynda Berry, author of Making Comics, teaches a method for creating comics that describes a similar relationship between artist and art. “Part of our work is to take time, to wait like any bird-watcher, to hold still and be taken in,” she says (Making Comics, 21). Her drawing exercises reconnect students with an ability we all possess as young children — to “speak image” — through warm-ups, prompts, and ritual around sitting down to create. Nick Sousanis, author of Unflattening, also argues that we are born with the abilities we need to think and create outside the box. “Drawing is a way of seeing and thus, a way of knowing, in which we touch more directly the perceptual and embodied processes underlying thinking,” he says (Sousanis, 78). In other words, we’re learning from the art as we create it. In relation to my own work, which concerns itself with the experience of Hanford Nuclear Plant workers, this shift in thinking may help me and my audience to connect more personally with the people whose stories I tell.

Notes and exercises from Making Comics by Linda Berry. Her method focuses on learning to convey meaning through drawings—and discover new meaning in the drawings themselves.

One of these books teaches drawing and the other teaches teaching itself, but their arguments share a core belief: That traditional teaching results in a contraction of intellect and creativity that inhibits profound insight and growth. Like Berry, Sousanis says cultivating an expansive view toward teaching is a re-learning of what we’re each born to do. Speaking to a baby, he writes, “Too often we fall for the deception…that your thinking must be given to you, put in you, a recipe to fill you up (144).” By teaching and modeling an expansive, exploratory form of academic writing, Sousanis demonstrates that how we present academic research can contribute to the shift from the prescribed way of learning — which he visualizes as a contraction of footsteps onto an ever-narrowing path — into an expansion into new, unexplored ways of understanding the world.